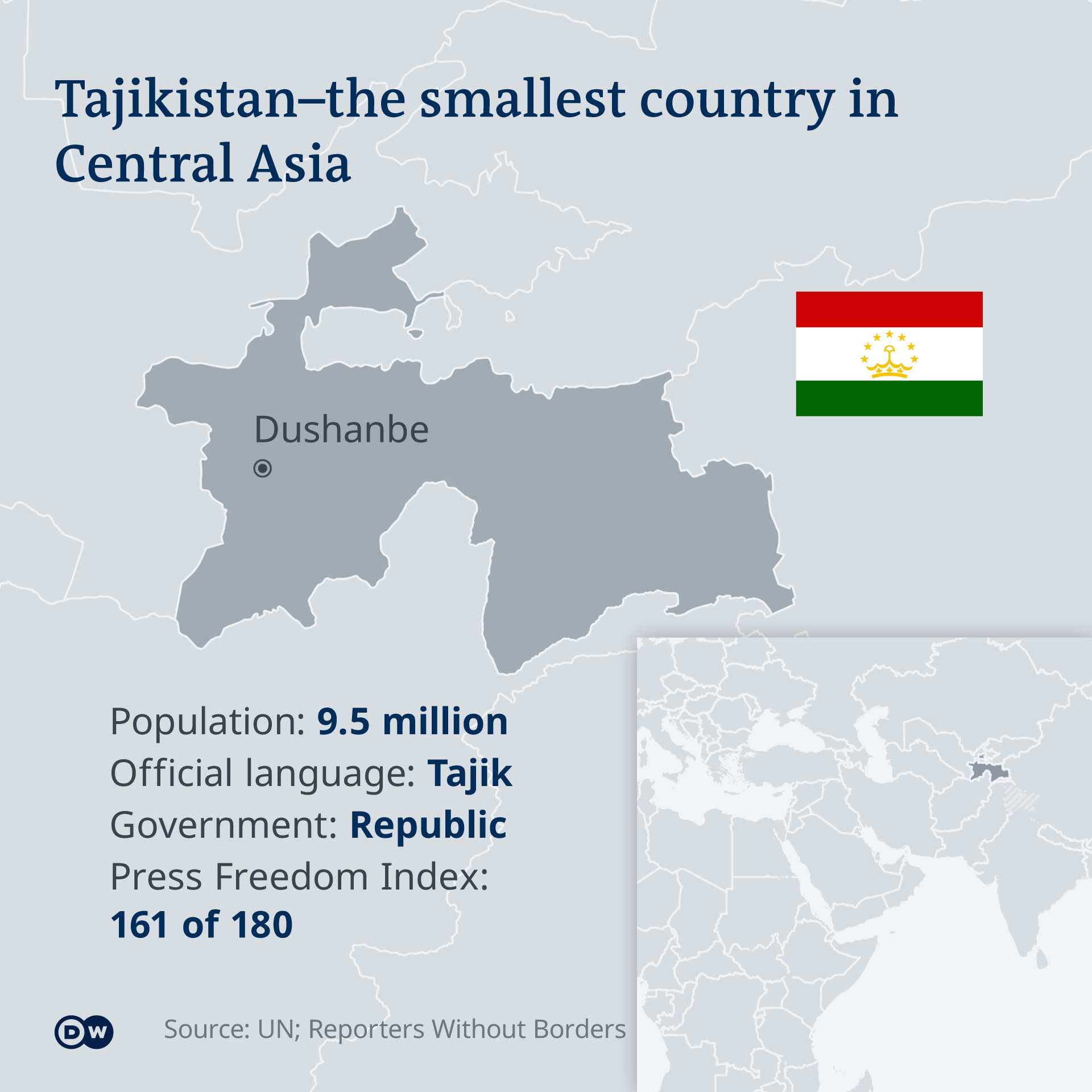

Press freedom in Tajikistan: From bad to worse

DW: How would you rate the state of press freedom in Tajikistan?

Marat Mamadshoev: In short, it's bad. And it's getting even worse. The media is under government control in every possible way. Content on electronic media such as television and radio stations is especially tightly controlled. Most of the media are owned by the government anyway.

Independent television and radio stations are forced to tighten their grip on self-censorship for fear of losing their license. So they mainly produce entertainment. But it is obvious that the prosecution of these media organizations for criticism also plays a role.

In freedom of speech ratings from around the globe, various reputable international organizations have put Tajikistan at the very end in recent years. And now, several dozen Tajik journalists, who worked in these publications, have in the meantime received asylum in Europe — including in Germany.

What about the internet? Can people access independent information online?

The spread of the internet in Tajikistan remains very low — even compared to neighboring countries. Despite this, authorities constantly block sites.

The government has also blocked access to the websites of a number of news agencies, both local and foreign. Moreover, even anonymizing software and VPN access are blocked. There is also a lot of pressure on bloggers and independent researchers.

Read more: Report: Tajikistan to fine journalists for unknown words

Are people sufficiently informed during the COVID-19 pandemic then? What is the official stance of the government here?

The Tajik government has long denied that Tajik citizens have at all been infected with COVID-19. The presence of COVID-19 patients in the country was only recognized one day before the arrival of representatives of the World Health Organization.

But earlier, social networks had already reported the deaths of people with symptoms similar to coronavirus. Authorities, however, claimed that these people died from other diseases. They usually mentioned pneumonia.

Nevertheless, almost all those who died from "pneumonia" were buried under the strict control of the authorities, and by people wearing special protective suits.

Why would the government try to hide a global pandemic?

Tajikistan is one of the poorest countries in the world, and possibly the poorest in the region. Many people live only off their daily earnings. They have no savings. Moreover, many live off their children, who migrate to Russia for work.

The government knows that by introducing strict quarantine rules it would actively have to help people not starve to death. And authorities either do not want to do that, or cannot afford to, because — like the people — they also have no financial reserves.

The overall economic performance of the country was bad already before the coronavirus but has now also worsened. Therefore, the authorities appear to think that such a policy of very lenient restrictive measures without the introduction of proper quarantine will help avoid undesirable social consequences.

How are journalists who report on COVID-19 in Tajikistan being treated?

This extreme climate enhances the self-censorship both on part of the journalists themselves and their editors. Several of my colleagues say they are constantly being threatened by telephone and on social networks.

Read more: Tajikistan frees journalist and comedian Khayrullo Mirsaidov

Note that at the same time, there are statements coming from officials that can be regarded as pressure on freedom of speech. The Prosecutor General’s Office warned that "with respect to those who are sowing panic across the country, measures will be taken against them as defined by the laws of Tajikistan."

For example, the other day, Asia-Plus journalist Abdullo Gurbati, known for his critical writing, was assaulted — for the second time. He had written a report on panic in markets in the capital Dushanbe because of rumors that there could be a shortage in flour due to the COVID-19 epidemic.

Of course, we cannot say unequivocally who actually attacked him, and why. However, similar attacks on journalists and activists have occurred in the past. The problem is that, as a rule, law enforcement agencies do not look for the culprits of these attacks.

Under this effective media blackout, is the health crisis in the country worse than we believe?

It's hard for me to really assess the situation, but from what I hear as a citizen and as a journalist, the situation on the ground is much worse than the reports of the Ministry of Health and Social Protection of Tajikistan. Our sources say that many doctors have to buy their protective clothing at their own expense.

There is a World Bank forecast "to the emergency response of COVID-19 in Tajikistan" that says that tens of thousands of people could die. I am absolutely sure that to deal effectively with the pandemic, maximum transparency is needed. Officials must communicate honest information to the media, and people must make the right decisions based on this.

Some international organizations such as the European Union are making aid donations to Tajikistan contingent on democratization in the country. Do you think the coronavirus crisis might help put spotlight on Tajikistan and encourage press freedom and other democratization processes?

The Tajik people need freedom of the press and democratization. But that's in their own hands. Outside attention may give some kind of short-term effect — but it will not be significant.

Marat Mamadshoev is a winner of O. Latifi award for the professional journalism. He works as a mentor and trainer on journalistic standards and ethics in journalism. Mamadshoev has worked as a correspondent and editor of the Asia-Plus newspaper, as editor of the Internews Tajikistan website, and as editor of Information Agency "Ozodagon."

Since 2019, he has been working for the Central Asian Bureau for Analytical Reporting (CABAR), which is run by the London-based Institute for War and Peace Reporting (I.W.P.R.).

The interview was conducted by Sertan Sanderson.

As has been the case in previous years with the physical Global Media Forum held annually at the World Conference Center Bonn, the digital edition of the Global Media Forum 2020 also receives support from the Federal Foreign Office, the German state of North Rhine-Westphalia, the Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development and the Stiftung Internationale Begegnung der Sparkasse in Bonn.